Policies of War

Naval Warfare & the Navies

"It must be understood that the ship itself it the weapon." — Raiders of Gor, page 192.

Introduction

NOTE: Much of the maritime information that John Norman used for his books dates back to ancient Greece. However, today, many rowing clubs, or triremes still utilize much of the nomenclature. In my own research, I found some art work of reliefs depicting rowers on an ancient Grecian ram-ship, as well as the ram-ship itself and a picture of one of the rams. I am including them on this page because I felt it would be of interest to be able to see what some of these ships may have looked like. Information not taken from John Norman's books of Gor has been taken from my list of resources at the bottom of this page.

Port Kar, being the most commonly mentioned port city with regards to the naval structure, as well as nautical information, will be the base for the information on this page.

Council of Captains

With its large population of seamen, some belonging to smaller fleets, and others to those larger fleets, captains of which belonged to the elite Council of the Captains, it's no wonder why Port Kar earned its reputation for its harshness of life, its band of rogues and thieves and outlaws. Order was kept in the city and the port itself by the Council of Captains. At one time, five Ubars stood in authority over this Council, however, after the failed coup of one such Ubar, the Council became the single ruling authority in Port Kar.

"I took my sea in the Council of the Captains of Port Kar.

It was now near the end of the first passage hand, that the following En'Kara, in which occurs the Spring Equinox. The Spring Equinox, in Port Kar as well as in most other Gorean cities, marks the New Year. In the chronology of Ar it was now the year 10,120. I had been in Port Kar for some seven Gorean months.

None had disputed my right to the seat of Surbus. His men had declared themselves mine. Accordingly I, who had been Tarl Cabot, once a warrior of Ko-ro-ba, the Towers of the Morning, sat now in the council of these captains, merchant and pirate princes, the high oligarchs of squalid, malignant Port Kar, Scourge of Gleaming Thassa.

In the council, in effect, was vested the stability and administration of Port Kar. Above it, nominally, stood five Ubars, each refusing to recognize the authority of the others, Chung, Eteocles, Nigel, Sullius Maximus and Henrius Sevarius, claiming to be the fifth of his line. The Ubars were represented on the council, to which they belonged as being themselves Captains, by five empty thrones, sitting before the semicircles of curule chairs on which reposed the captains. Beside each empty throne there was a stool from which a Scribe, speaking in the name of the Ubar, participated in the proceedings of the council. The Ubars themselves remained aloof, seldom showing themselves for fear of assassination.

A scribe, at a large table before the five thrones, was droning the record of the last meeting of the council.

There are commonly about one hundred and twenty captains who form the council, sometimes a few more, sometimes a few less. Admittance to the council is based on being master of at least five ships. Surbus had not been a particularly important captain, but he had been the master of a fleet of seven, now mine. These five ships, pertinent to council membership, may be either the round ships, with deep holds of merchandise, or the long ships, ram-ships, ships of war." — Raiders of Gor, pages 126-127.

Clienthood is the general rule of thumb amongst many of the captains in Port Kar. It is in reference to the practice of a ship captain paying fees, or taxes, or providing free services, to a Ubar, and in exchange receiving the protection of said Ubar.

Etymology: Middle English, from Middle French & Latin; Middle French client, from Latin client-, cliens; perhaps akin to Latin clinare to lean; Date: 14th century;

1. "One that is under the protection of another;

2. a person who engages the professional advice or services of another;

3. Client State." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"Many of the captains, incidentally, were client to one Ubar or another. I myself did not choose to apply for clienthood with a Ubar of Port Kar. I did not expect to need their might, nor did I wish to extend them my service." — Raiders of Gor, page 129.

The Seaman and the Sea

To the seaman, Thassa was his life, his world, his first love above all else. It is always the wish of a seaman that before his death, that he can look upon the sea one last time, deeming that the sea would harbor his soul. To allow a seaman such, is considered honorable amongst fellow seaman.

His hand lifted again, even more weakly, extended to me. There was agony in his eyes. His lips moved, but there was no sound. The girl looked up at me and said, "Please, I am too weak."

"What does he want?" I asked, impatient. He was pirate, slaver, thief, murderer. He was evil, totally evil, and I felt for him only disgust.

"He wants to see the sea," she said… I bent and put the arm of the dying man about my shoulders and, lifting him, with the girl's help, went back through the kitchen of the tavern and, one by one, climbed the high, narrow stairs to the top of the building. We came to the roof, and there, near its edge, holding Surbus between us, we waited. The morning was cold, and damp. It was about daybreak. And then the dawn came and, over the buildings of Port Kar, beyond them, and beyond the shallow, muddy Tamber, where the Vosk empties, we saw, I for the first time, gleaming Thassa, the Sea. The right hand of Surbus reached across his body and touched me. He nodded his head. His eyes did not seem pained to me, nor unhappy. His lips moved, but then he coughed, and there was more blood, and he stiffened, and then, his head falling to one side, he was only weight in our arms. We lowered him to the roof.

"What did he say?" I asked.

The girl smiled at me. "Thank you," she said. "He said Thank you."

I stood up wearily, and looked out over the sea, gleaming Thassa. "She is very beautiful," I said.

"Yes," said the girl, "yes."

"Do the men of Port Kar love the sea?" I asked.

"Yes," she said, "they do." — Raiders of Gor, pages 123-124.They were seamen of Port Kar…They had come with Surbus to the tavern the night before. They were portions of his crew. One of the men stood forward…"I am Tab," he said, "I was second to Surbus… You let him see the sea?" said Tab.

"Yes," I said.

"Then," we are your men." — Raiders of Gor, page 125."The sea! The sea!" cried the man. "The sea!" He stumbled forth from the thickets, and, behind them, the lofty trees of the forest. He stood alone, high on the beach, his sandals on its pebbles, a lonely figure… He had then stumbled down the beach, falling twice, until he came to the shallows and the sand, among driftwood, stones and damp weed, washed ashore in the morning tide. He stumbled into the water, and then fell to his knees, in some six inches of water. In the morning wind, and the fresh cut of the salt smell, the water flowed back from him, leaving him on the smooth wet sand. He pressed the palms of his hands into the sand and pressed his lips to the wet sand. Then, as the water moved again, in the stirrings of Thassa, the sea, in its broad swirling sweep touching the beach, he lifted his head and stood upright, the water about his ankles. He turned to face the Sardar, thousands of pasangs away. He did not see me, among the darkness of the trees. He lifted his hands to the Sardar, to the Priest-Kings of Gor. Then he fell again to his knees in the water and, lifting it with his hands, hurled it upward about him, and I saw the sun flash on the droplets. He was laughing, haggard. And then he turned about, and, slowly, step by step, marking the drier sand with his wet sandals, made his way again back up the beach.

"The sea!" he cried into the forest. "The sea!"

"The sea!" cried others, now stumbling from the forests. They had not thought, many of them, to again see the sea. — Hunters of Gor, pages 242-243.

Naval Officers

Admirals, Captains and other naval officers of import are generally extravagantly dressed, with cordings of gold upon their dress, golden tassels and sashes, and gold markings on their helmets. In addition, Captains are accorded the honor of wearing a crest of sleen hair on their helmet.

"Though his helmet still bore the two golden slashes, in now bore as well a crest of sleen hair, permitted only to captains." — Raiders of Gor, page 129.

"I wore the purple of a fleet admiral, with a golden cap with tassel, and gold trim on the sleeves and borders of my robes, with cloak to match." — Raiders of Gor, page 213.

"He was conversing with the bearded officer, tall and with the golden slashes on the temples of his helmet." — Raiders of Gor, page 60.

Generally, women on ships traveled as slaves. However, upon the occasion that a free woman, especially one of high caste, were to be taking passage upon a ship, she was afforded a cabin, located in the stern castle of the galleys.

"High born ladies commonly sailed in cabins, located in the stern castle of the galleys." — Raiders of Gor, page 180.

Pirates Not of the Caribbean

One of the many dangers upon Thassa are pirates. Pirates on Gor paint their ships green as a means of camouflage to hide them upon the waters. This makes them nearly invisible.

"Green, on Thassa, is the color of pirates. Green hulls, sails, oars, even ropes. In the bright sun reflecting off the water, green is a color most difficult to detect on gleaming Thassa. The green ship, in the bright sun, can be almost invisible." — Raiders of Gor, page 190.

Importance of Musicians

Musicians play an important part on a ship. Often they are used to signal other ships with a set of notes, or to simply inspire a battle with a song. Flutes, drums and trumpets are the most common instruments used.

"… I had the flutists and drummers, not uncommon on the ram-ships of Thassa, strike up a martial air." — Raiders of Gor, page 197.

"… I had communicated with my other ships by flag and trumpet, some of them conveying my messages to others more distant." — Raiders of Gor, page 205.

Superstitions

It is a belief amongst the mariners that ships are alive, and therefore, eyes are painted on to enable this living entity to "see" as it moves through the waters.

"The eyes of the ship, painted on either side of the bow, would now have turned toward the opening of the harbor of Telnus. Ships of Gor, of whatever class or type, always have eyes painted on them, either in a head surmounting the prow, as in tarn ships, or, as in the Rena, as in round ships, on either side of the bow. It is the last thing that is done for the ship before it is first launched. The painting of the eyes reflects the Gorean seaman's belief that the ship is a living thing. She is accordingly given eyes, that she may see her way." — Raiders of Gor, page 183.

Naval Encampments

It is common for Gorean seamen to beach their craft in the evening and make camp.

"It is common among Gorean seamen to beach their craft in the evening, set watches, make camp, and launch again in the morning." — Raiders of Gor, page 192.

Naval encampments are uniform in set-up as described in the following passage:

"The riverside camp was not untypical of a semi-permanent Gorean naval camp. The Tesephone had been beached, and lay partly on her side, thus permitting scraping, recalking and resealing of the hull timber, first on one side and then, later, when turned, on the other. These repairs would be made partly from stores carried on board, partly from stores purchased in Laura. There would also, of course, be much attention given to the deadwook of the ship, and to her lines and rigging, and the fittings and oars. Meanwhile, portions of the crew not engaged in such labors, would be carrying stones from the shore and cutting saplings in the forest, to build the narrow rectangular wall which shields such camps. Cooking, and most living, is done within the camp, within the wall and at the side of the Tesephone. The wall is open, of course, to the water. Canvas sheets, like rough awnings on stakes, are tied to the Tesephone, and these provide shade from the sun and protection in the case of rain." — Hunters of Gor, page 85.

The practice of lining up of marsh barges to create a defensive fort is detailed in brief as follows:

"The barges, during the afternoon, had been eased into a closer line, the stem on one lying abeam of the stern of the next, being made fast there by lines. This was to prevent given barges from being boarded separately, where the warriors on one could not come to the aid of the other. They had no way of knowing how many rencers might be in the marshes. With this arrangement they had greater mobility of their forces, for men might leap, say, from one foredeck of one barge to the tiller deck of the other. If boarding were attempted toward the center of the line, the boarding party could thus be crushed on both flanks by warriors pouring in from adjacent barges. This arrangement, in effect, transformed the formerly purposes, a long, single, narrow, wooden-walled fort." — Raiders of Gor, page 73.

Nautical Weaponry

This section is under construction.

• Ship Bow

A short, stout bow, making its use maneuverable even in close quarters, with a rapid rate of fire. The ship bow excels above the peasant bow (long bow) in impact, range and accuracy.

"The bows were put to their feet. They were short, ship bows, stout and manoeuvrable, easy to use n crowded quarters, easy to fire across the bulwarks of galleys locked in combat. I had seen only such bows in the holding of Policrates. Their rate of fire, of course, is much superior to that of the crossbow, either of the drawn or windlass variety. All things considered, the ship bow is an ideal missile weapon for close-range naval combat. It is superior in this respect even to the peasant bow, or long bow, which excels it in impact, range and accuracy." — Rogue of Gor, pages 307-308.

• Warships

The ram-ships are in their own right, a weapon. However, even round ships can be formidable opponents in times of war, often carrying springals, small catapults, and onangers, as well as armed archers and those trained in the use of javelins. Please refer to the Naval Warfare page for complete information.

"It must be understood that the ship itself it the weapon." — Raiders of Gor, page 192.

"On the other hand, whereas the round ships do not carry rams and are much slower and less maneuverable than the long ships, they are not inconsequential in a naval battle, for their deck areas and deck castles can accommodate springals, small catapults, and chain-slings onagers, not to mention numerous bowmen, all of which can provide a most discouraging and vicious barrage, consisting normally of javelins, burning pitch, fiery rocks and crossbow quarrels." — Raiders of Gor, page 133.

The Ships

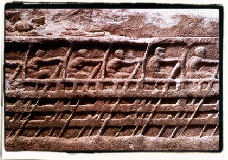

Fleets of various sorts can be found upon the waters of Thassa. There are merchant fleets, each with their chosen cargoes, patrol fleets, et al.  Pictured: Lenormant Relief from Athenian Acropolis (approximately 410-400 B.C.). The preserved portion is starboard midships displaying three (3) banks of rowers.

Pictured: Lenormant Relief from Athenian Acropolis (approximately 410-400 B.C.). The preserved portion is starboard midships displaying three (3) banks of rowers.

"… which ships comprise the members of the grain fleet, the oil fleet, the slave fleet, and others, as well as numerous patrol and escort ships." — Raiders of Gor, page 133.

"… the single-banked, three-men-three-oars arrangement [to a bench] is almost universal in fighting ships on Thassa." — Raiders of Gor, page 195.

Often a fate of prisoners, is to be sent to Port Kar to work the galleys as a galley slave. In port cities, such as Port Kar, rather than an elaborate slave auction house, slaves are simple sold on the wharves, generally males to be sold as galley slaves (please also refer to the Slave Auction and the Male Slave pages for more information). A harsh life, consisting of eating onions, black bread and perhaps some peas upon occasion, rowing the mighty ships of the Thassa. Such slaves generally row the round ships, though, never do they row the tarn ships or warships. For a free man to leave their fate at the hands of slaves in times of battle was unthinkable. Tarl Cabot, aka Bosk of Port Kar, did make a bit of a few changes, much to the dislike of some; one of which was employing free men to row the great round ships.

"I had made one innovation in practices common to Port Kar. I used free men on the rowing benches on my round ships, of which I had four, not slaves, as is traditional." — Raiders of Gor, page 140.

"The fighting ship, incidentally, the long ship, the ram-ship, has never been, to my knowledge, in Port Kar, or Cos, or Tyros, or elsewhere on Gor, rowed by slaves; the Gorean fighting ship always has free men at the oars." — Raiders of Gor, page 140.

Lurius settled himself, breathing heavily, again in his throne. "Put him in a market chain," said Lurius, "and sell him at the slaves' wharf." — Raiders of Gor, page 176.

"When," snarled Lurius, "you find yourself chained in the rowing hold of a round ship, you may, my fine captain of Port Kar, bethink yourself less brave and clever than now you do." — Raiders of Gor, page 176.

• The Long Ships

Gorean warship. See: "Ram-Ships."

"The fighting ship, incidentally, the long ship, the ram-ship, has never been, to my knowledge, in Port Kar, or Cos, or Tyros, or elsewhere on Gor, rowed by slaves; the Gorean fighting ship always has free men at the oars." — Raiders of Gor, page 140.

"These five ships, pertinent to council membership, may be either the round ships, with deep holds of merchandise, or the long ships, ram-ships, ships of war. Both are predominantly oared vessels, but the round ship carries a heavier, permanent rigging, and supports more sail, being generally two-masted. The round ship, of course, is not round, but it does have a much wider beam to its length of keel, say, about one to six, whereas the ratios of the war galleys are about one to eight."

— Raiders of Gor, page 127.

[Depiction of a trireme] An example of the sway of maritime law on the popular culture of the ancients comes to us through descriptions of the legal authority for crewing vessels. Contrary to portrayals in modern cinema of slave galleys rowing a trireme (see the Greek section of this page ) into battle, freeman crewed naval vessels, and usually these were citizens performing public duty or paid professionals. When Odysseus makes a plea for a ship home, the Prince of Phaecia immediately orders such passage: "for no guest of mine languishes here for lack of it," and outfits the fastest sailing ship, drafting a crew of two-hundred-fify (250) of the younger townsmen, who have made their names at sea.

The practice was different with respect to merchant vessels. Classical Greek and Roman literature suggest the widespread use of slaves on merchant vessels. Demosthenes notes the use of freighters manned by slaves,and Julius Caesar comments on the slaughter of all the Caesar's supply ships in 48 B.C.

• The Ram-Ships

The warship of Gor, also referred to as a long ship. Because this is a warship, it is rowed by free men. A long, sleek oared vessel, it is much faster and more easily maneuverable than the round ships, with a beam to keel ratio of 1 to 8. Because of the nature of this ship, it is always oared by free men, rather than slaves. Referred to as "ram-ships" as these ships are used to ram into enemy ships to cause destruction. The single-banked ram-ship is called a tarn ship. See also: "Tarn Ship."

Ram: An appurtenance fixed to the front end of a fighting vessel and designed to damage enemy ships when struck by it. It was possibly first developed by the Egyptians as early as 1200 BC, but its importance was most clearly emphasized in Phoenician, Greek, and Roman galleys (seagoing vessels propelled primarily by oars). The ram enjoyed a brief revival in naval warfare in the mid-19th century, notably in the American Civil War and the Austro-Italian War of 1866. At this time rams were mounted on armoured, steam-propelled warships and used effectively against wooden sailing ships. Improvements in naval ordnance and the spread of metal-hulled ships soon made the ram obsolete again, however." — Encyclopaedia Britannica © 2004-2006.

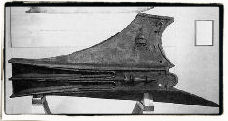

Pictured: Athlit Ram; Discovered in 1980 near Haifa.  Dimensions: 7.5' x 2.5', weighs 1000 lbs, 7-10 mm high-grade bronze. The timbers found within the ram contain the remains of sixteen (16) bow timbers, including wales. The three-finned design indicates that the primary goal was to strike rather than penetrate the enemy ships.

Dimensions: 7.5' x 2.5', weighs 1000 lbs, 7-10 mm high-grade bronze. The timbers found within the ram contain the remains of sixteen (16) bow timbers, including wales. The three-finned design indicates that the primary goal was to strike rather than penetrate the enemy ships.

"These five ships, pertinent to council membership, may be either the round ships, with deep holds of merchandise, or the long ships, ram-ships, ships of war. Both are predominantly oared vessels, but the round ship carries a heavier, permanent rigging, and supports more sail, being generally two-masted. The round ship, of course, is not round, but it does have a much wider beam to its length of keel, say, about one to six, whereas the ratios of the war galleys are about one to eight." — Raiders of Gor, page 127.

"The fighting ship, incidentally, the long ship, the ram-ship, has never been, to my knowledge, in Port Kar, or Cos, or Tyros, or elsewhere on Gor, rowed by slaves; the Gorean fighting ship always has free men at the oars." — Raiders of Gor, page 140.

"Since the principal weapons of the ram-ship are the ram and shearing blades, she is most dangerous taken head on." — Raiders of Gor, page 203.

"In questions of ramming, I suppose the heavier ship would deliver the heaviest blow, but, even this might be contested for the lighter ship would, presumably, be moving more rapidly. Further, of course, the chances of being rammed by a lighter ship are greater than those of being rammed by a heavier ship, because of the greater speed and maneuverability of the former." — Raiders of Gor, page 195.

"Round ships, like ram-ships, differ among themselves considerably. But most are, as I may have mentioned, two masted, have permanent masts and, like the ram-ships, are lateen rigged. They, though they carry oarsmen, generally slaves, are more of a sailing ship than the ram-ship. They can, generally, sail satisfactorily to windward, taking full advantage of their lateen rigging, which is particularly suited to windward work. The ram-ship, on the other hand, is difficult to sail to windward, even with lateen rigging, because of its length, its narrowness and its shallow draft. In tacking to windward her leeward oars and rowing frame are likely to drag in the water, cutting down speed considerably and not infrequently breaking oars. Accordingly the ram-ship most commonly sails only with a fair wind. Further, she is less seaworthy than the round ship, having a lower freeboard area, being more easily washed with waves, and having a higher keel-to-beam ratio, making the danger of breaking apart in a high sea greater than it would be with a round ship. There are in the building of ships, as in other things, values to be weighed. The ram-ship is not built for significant sail dependence or maximum seaworthiness. She is built for speed, and the capacity to destroy other shipping. She is not a rowboat but a racing shell; she is not a club, but a rapier.

The free crews of these ships, of course, were hopelessly outnumbered by my men. The round ship, although she often carries over one hundred, and sometimes over two hundred, chained slaves in her rowing hold, seldom, unless she intends to enter battled, carries a free crew of more than twenty to twenty-five men. Moreover, these twenty to twenty-five are often largely simply sailors and their officers, and not fighting men. The Dorna, by contrast, carried a free crew of two hundred and fifteen men, most of whom were well trained with weapons." — Raiders of Gor, page s205-207.

• The Round Ships

Ships used primarily for hauling merchandise and other cargo. These ships are large and heavy, slow and less maneuverable than the long ships with deep holds for merchandise. Although these ships are not truly round, these ships do have a wider beam compared to its keel length. These ships, oared vessels, carry a heavy, permanent rigging, which supports more sail. A medium-class round-ship would mean that she would be able, in Earth figures, to carry approximately 100-150 tons below deck. Although these are not necessarily a war ship, they do provide useful purpose in times of war with their large, wide decks which can holds such things as seige engines, as well as archers and such. Traditionally, these ships are oared by slaves.

"These five ships, pertinent to council membership, may be either the round ships, with deep holds of merchandise, or the long ships, ram-ships, ships of war. Both are predominantly oared vessels, but the round ship carries a heavier, permanent rigging, and supports more sail, being generally two-masted. The round ship, of course, is not round, but it does have a much wider beam to its length of keel, say, about one to six, whereas the ratios of the war galleys are about one to eight." — Raiders of Gor, page 127.

"The Rena of Temos, like most round ships, had two permanent masts, unlike the removable mast of the war galleys. The main mast was a bit forward of amidships, and foremast was some four or five yards abaft of the ship's yoke. Both were lateen rigged, the yard of the foresail being about half the length of the yard of the mainsail." — Raiders of Gor, page 184.

"On the other hand, whereas the round ships do not carry rams and are much slower and less maneuverable than the long ships, they are not inconsequential in a naval battle, for their deck areas and deck castles can accommodate springals, small catapults, and chain-slings onagers, not to mention numerous bowmen, all of which can provide a most discouraging and vicious barrage, consisting normally of javelins, burning pitch, fiery rocks and crossbow quarrels." — Raiders of Gor, page 133.

"I now had the means whereby I might purchase yet two more ships for my fleet. They would be deep-keeled round ships, with mighty holds, and high, broad sails. I had already, to a great extent, selected crews. I had projected voyages for them to Ianda and to Torvaldsland. Each would be escorted by a medium galley." — Raiders of Gor, page 142.

"Round ships, like ram-ships, differ among themselves considerably. But most are, as I may have mentioned, two masted, have permanent masts and, like the ram-ships, are lateen rigged. They, though they carry oarsmen, generally slaves, are more of a sailing ship than the ram-ship. They can, generally, sail satisfactorily to windward, taking full advantage of their lateen rigging, which is particularly suited to windward work…" — Raiders of Gor, page 205.

"The round ship, although she often carries over one hundred, and sometimes over two hundred, chained slaves in her rowing hold, seldom, unless she intends to enter battled, carries a free crew of more than twenty to twenty-five men. Moreover, these twenty to twenty-five are often largely simply sailors and their officers, and not fighting men." — Raiders of Gor, page 207.

• The Tarn Ships

A variation of the ram-ship, with the ram shaped to resemble a tarn's head; single banked. Fighting ships; primarily used by pirates and slavers. See also: "Ram-Ship."

"The fleets of tarn ships of Port Kar are the scourge of Thassa, beautiful, lateen-rigged galleys that ply the trade of plunder and enslavement…" — Raiders of Gor, page 6.

"The Dorna, a tarn ship, is not untypical of her class. Accordingly I shall, in brief, describe her. I mention, however, in passing, that a great variety of ram-ships ply Thassa, many of which, in their dimensions, their lines, their rigging and their rowing arrangements, differ from her considerably. The major difference, I would suppose, is that between the singly-banked and the most doubly- or trebly-banked vessel. The Dorna, like most other tarn ships, is single-banked; and yet her oar power is not inferior to even the trebly-banked vessels; how this is I shall soon note.

" She carries a single, removable mast, with its long yard. It is lateen rigged. Her keep, one hundred and twenty-eight feet Gorean, and her beam, sixteen feet Gorean, mark her as heavy class. Her freeboard area, that between the water line and the deck, is five feet Gorean. She is long, low and swift. She has a rather straight keel, and this, with her shallow draft, even given her size, makes it possible to beach her at night, if one wishes. It is common among Gorean seamen to beach their craft in the evening, set watches, make camp, and launch again in the morning.

"The Dorna's ram, a heavy projection in the shape of a tarn's beak, shod with iron, rides just below the water line. Behind the ram, to prevent it from going too deeply into an enemy ship, pinning the attacker, is, shaped like the spread crest of a tarn, the shield. The entire ship is built in such a way that the combined strength of the keel, sternpost and strut-frames centers itself at the ram, or spur. The ship is, thus, itself the weapon. The bow of the Dorna is concave, sloping down to meet the ram. Her stern describes what is almost a complete semicircle. She has two steering oars, or side rudders. The sternpost is high, and fanlike; it is carved to represent feathers; the actual tail feathers of a tarn, however, would be horizontal to the plane, not vertical; the prow of the tarn ship resembles the ram and shield, though it is made of painted wood; it is designed and painted to resemble the head of a tarn. Tarn ships are painted in a variety of colors; the Dorna, of course, was green. "Besides her stem and stern castles the Dorna carried two movable turrets amidships, each about twenty feet high. She also carried, on leather-cushioned, swivel mounts, two light catapults, two chain-sling onagers, and eight springals. Shearing blades, too, of course, were a portion of her equipment. These blades, mentioned before, are fixed on each side of the hull, abaft of the bow and forward of the oars. They resemble quarter moons of steel and are fastened into the frames of the ship itself. They are an invention of Tersites of Port Kar. They are now, however, found on most recent ram-ships, of whatever port of origin. Although the Dorna's true beam is sixteen feet Gorean, her deck width is twenty-one feet Gorean, due to the long rectangular rowing frame, which carries the thole ports: the rowing frame is slightly higher than the deck area and extends beyond it, two and one half feet Gorean on each side; it is supported by extensions of the hull beams; the rowing frame is placed somewhat nearer the stem that the sternpost; the extension of the rowing frame not only permits greater deck area but, because of the size of the oars used, is expedient because of matters of work space. — Raiders of Gor, pages 192-193.

"The size and weight of the oars used will doubtless seem surprising, but, in practice, they are effective and beautiful levers. The oars are set in groups of three, and three men sit a single bench. These benches are not perpendicular to the bulwarks but slant obliquely back toward the stern castle. Accordingly their inboard ends are father aft than their outboard ends. This slanting makes it possible to have each of the three oars in an oar group parallel to the others. The three oars are sometimes of the same length, but often they are not. The Dorna used oars of varying lengths; her oars, like those of many tarn ships, varied by about one and one-half foot Gorean, oar to oar; the most inboard oar being the longest; the outboard oar being the shortest. The oars themselves usually weigh about one stone a foot, or roughly founds pounds a foot. The length of those oars on a tarn ship commonly varies from twenty-seven to thirty foot Gorean. A thirty-foot Gorean oar, the most inboard oar, would commonly weigh thirty stone, or about one hundred and twenty pounds. The length and weight of these oars would make their operation impractical were it not for the fact that each of them, on its inboard end, is weighted with lead. Accordingly the rower is relieved of the weight of the oar and is responsible only for its work. This arrangement, one man to an oar, and oars in groups of tree, and oars mounted in the rowing frame, long and beautiful sweeps, had been found extremely practical in the Gorean navies. It is almost universal on ram-ships. The rowing deck, further, is open to the air, thereby differing from the rowing holds of round ships. This brings many more free fighting men, the oarsmen, into any action which might be required. They, while rowing, are protected, incidentally, by a parapet fixed on the rowing frame. Between each pair of benches, behind the parapet, is one bowman. The thole ports in a given group of three are about ten inches apart and the groups themselves, center to center, are a bit less than four feet apart. Then Dorna carried twenty groups of three to a side, and so used one hundred and twenty oarsmen. — Raiders of Gor, page 193-194.

"From this account it may perhaps be conjectured why the oar power of a single-banked ram-ship is often comparable or superior to that of a doubly- or trebly-banked ship. The major questions involve the number and size of oars that can be practically mounted, balanced against the size of ship required for the differing arrangements. The use of extended rowing frame, permitting the leverage necessary for the great oars, and the seating of several oarsmen, each with his own oar, on a given bench, conserving space, are important in this regard. If we suppose a trebly-banked ship with one hundred and twenty oarsmen, say, in three banks of twenty each to a side, I think we can see she would have to be a rather large ship, and a good deal heavier than the single-decked, three-men-to-a-bench type, also with one hundred and twenty oarsmen. She would thus, also, be slower. And this does not even take into consideration the longer, larger oar possible with the projecting rowing frame. To be sure, they are many factors involved here, and one might suppose triple banks following the model of the single-banked, three-men-oars-to-a-bench type, and so on, but, putting aside questions of the size of vessel required for such arrangements, we may simply note, without commenting further, that the single-banked, three-men-three-oars arrangement is almost universal in fighting ships on Thassa. The other type of ship, though found occasionally, does not seem, at least currently, to present a distinct challenge to the low, swift, single-banked ships. In questions of ramming, I suppose the heavier ship would deliver the heaviest blow, but, even this might be contested for the lighter ship would, presumably, be moving more rapidly. Further, of course, the chances of being rammed by a lighter ship are greater than those of being rammed by a heavier ship, because of the greater speed and maneuverability of the former. Other disadvantages to the double- and triple-banked systems, of course, are that many of your oarsmen, if not all, are below decks and thus unable to enter into necessary actions as easily as they might otherwise do; further, in case of ramming or wreck, it is a good deal more dangerous to be below decks than above decks. At any rate, whatever the reasons or rationale, the single-banked tarn ship, of which the Dorna is an example, is the dominant type on Thassa." — Raiders of Gor, pages 194-195.

• The Tharlarion Ships

A variation of the long-boat; the prow created to resemble a tharlarion.

"Outside the holding, on the broad promenade before of the holding, bordering on the lakelike courtyard, with the canal gate beyond, I ordered a swift, tharlarion-prowed longboat made ready… The tharlarion head of the craft turned toward the canal gate." — Raiders of Gor, page 253.

• The Ships of the Torvaldslanders

Smaller in size than the ships of the southern regions, with square-shaped sails, rather than triangular, these heavily built oared ships are not only seen in the frozen north, but in the southern regions, such as Schendi, as well. The ships of the Torvaldslanders are the only ships on Gor with single rudders.

"The Gorean galley, carvel built, long and of shallow draft, built for war and speed, is not built to withstand the frenzies of Thassa. The much smaller craft of the men of Torvaldsland, clinker built, with overlapping, bending planking, are more seaworthy. They must be, to survive in the bleak, fierce northern waters, wind-whipped and skerry-studded. They ship a great deal more water than the southern carvel-built ships, but they are stronger, in the sense that they are more elastic. They must be baled, frequently, and are, accordingly, not well suited for cargo. The men of Torsvaldland, however, do not find this limitation with respect to cargo a significant one, as they do not, generally, regard themselves as merchants or traders. They have other pursuits, in particular the seizure of riches and the enslavement of beautiful women.

Their sails, incidentally, are square, rather than triangular, like the lateen-rigged ships of the south. They cannot said as close to the wind as the southern ships with lateen rigging, but, on the other hand, the square sails makes it possible to do with a single sail, taking in and letting out canvas, as opposed to several sails, which are attached to and removed from the yard, which is raised and lowered, depending on weather conditions.

It might be mentioned too, that their ships hare, in effect a prow on each end. This makes it easier to beach them than would otherwise be the case. This is a valuable property in rough water close to shore, particularly where there is danger of rocks. Also, by changing their position on the thwarts, the rowers, facing the other direction, can, with full power, immediately reverse the direction of the ship. They need not wait for it to turn. There is a limitation her, of course, for the steering oar, on the starboard side of the ship, is most effective when the ship is moving in its standard 'forward' direction. Nonetheless, this property to travel in either direction with some facility, is occasionally useful. It is, for example, extremely difficult to ram a ship of Torvaldsland. This is not simply because of their general size, with consequent maneuverability, and speed, a function of oarsmen, weight and lines, but also because of this aforementioned capacity to rapidly reverse direction. It is very difficult to take a ship in the side which, in effect, does not have to lose time in turning.

Their ships are seen as far to the south as Shendi and Bazi, as far to the north as the great frozen sea, and are known as far to the west as the cliffs of Tyros and the terraces of Cos. The men of Torvaldsland are rovers and fighters, and sometimes they turn their prows to the open sea with no thought in mind other than seeing what might lie beyond the gleaming horizon." — Hunters of Gor, pages 256-257."Most Gorean vessels, on the other hand, like many early vessels of Earth, are double ruddered. A reference to the 'rudder side' would thus, in Gorean, be generally uninformative. It might be noted, however, if it is of interest, that the swift, square-rigged ships of Torvaldsland are single ruddered, and on the right side. A reference to the 'rudder side' or 'steering-board,' or 'steering-oar,' side would be readily understood, at least by sailors, if applied to such a ship." — Slave Girl of Gor, page 362.

Ship Classes

There are three classes of ships used in the navies and merchant fleets of Gor.

• Light Class

The smallest, lighest war galleys, used mostly in patrols and communciations.

"Men scrambled on the long yard of the lateen-rigged light galley, a small, swift ram-ship of Port Kar." — Hunters of Gor, page 18.

"This galley, one of my swiftest, the Tesephone of Port Kar, had forty oars, twenty to a side. She was single ruddered, the rudder hung on the starboard side. Like others of her class, she is of quite shallow draft. Her first hold is scarcely a yard in height. Such ships are not meant for cargo, lest it be treasure or choice slaves. They are commonly used for patrols and swift communication. The oarsmen, as in most Gorean war galleys, are free men. Slaves serve commonly only in cargo galleys. The oarsmen sit their thwarts on the first deck, exposed to the weather. Most living, and cooking, takes place here. In foul weather, if there is not high wind, or in excessive heat, a canvas covering, on poles, is sometimes spread over the thwarts. This provides some shelter to the oarsmen. It is not pleasant to sleep below decks, as there is little ventilation. The 'lower hold' is not actually a hold at all, even of the cramped sort of the first hold. It is really only the space between the keel and the deck of the first hold. It is approximately an eighteen-inch crawl space, unlit and cold, and damp. This crawl space, further, in its center, rather amidships and toward the stern, contains the sump, or bilge. In it the water which is inevitably shipped between the calked, tarred, expanding, contracting, sea-buffeted wooden planking, is gathered. It is commonly foul, and briny. The bilge is pumped once a day in calm weather; twice, or more, if the sea is heavy. The Tesephone, like almost all galleys, is ballasted with sand, kept in the lower hold. If she carries much cargo in the first hold, forcing her lower in the water, sand may be discarded. Such galleys normally function optimally with a freeboard area of three to five feet. Sand may be added or removed, to effect the optimum conditions for either stability or speed. Without adequate ballast, of course, the ship is at the mercy of the sea. The sand in the lower hold is usually quite cool, and, buried in it, are commonly certain perishables, such as eggs, and bottled wines." — Hunters of Gor, pages 19-20.

• Medium Class

A medium class of galley is determined not by the freight it carries, but by the keel length and beam width.

"In a round ship this means she would be able, in Earth figures, to freight between approximately one hundred and one hundred and fifty tons below decks. A medium class round ship should be able to carry from 5,000 to 7,500 Gorean Weight." — Raiders of Gor, page 127.

"Medium class for a long ship, or ram-ship, in determined not by freight capacity but by keel length and width of beam; a medium-class long ship, or ram-ship, will have a keel length of from eighty to one hundred and twenty feet Gorean; and a width of beam of from ten to fifteen feet Gorean." — Raiders of Gor, page 127.

• Heavy Class

A heavy class of galley is determined by keel length and beam width; most ram-ships are of medium or heavy class.

"Indeed, the galleys of Port Kar, medium and heavy class, carried shearing blades, which had been an invention of Tersites." — Raiders of Gor, page 136.

"Her keep, one hundred and twenty-eight feet Gorean, and her beam, sixteen feet Gorean, mark her as heavy class." — Raiders of Gor, page 192.

The Sails

The sails of the Gorean ships fall into three (3) main types, based upon weather conditions and the need for speed: the Fair-Weather Sail, which is used during gentler weather conditions; the Tarn Sail, which is the most common sail used on ships; and the Storm Sail, which is used during times of heavy storms. The Tharlarion Sail is actually a smaller version of the Tarn Sail, and is much more manageable than its larger counterpart, and often used in brutal winds. Prior to a ship going into battle, the mast is brought down, the sail stored below decks, and the bulwark and deck of the ship covered in wet hides.

"A war ship going into battle, incidentally, always takes its mast down and stores its sail below decks. The bulwarks and deck of the ship are often covered with wet hides." — Raiders of Gor, pages 133-134.

Lateen refers to a triangular shaped sail; this sail falls in all three main classes of sails. It is considered by mariners to be the most beautiful type of rigging, as compared to the squared rigged ships.

"A triangular shaped sail." — American Heritage College Dictionary, Third Edition ©2001

"Tersites had also, it might be mentioned, though he had not presented these ideas in his appearance before the council, argued for a rudder hung on the sternpost of the tarn ship, rather that the two side-hung rudders, and had championed a square rigging, as opposed to the beautiful lateen rigging common on the ships of Thassa. Perhaps this last proposal of Tersites' had been the most offensive of all to the men of Port Kar. The triangular lateen sail on its single sloping yard is incredibly beautiful." — Raiders of Gor, page 137.

"As I watched, the long, starting-out line of round ships of Port Kar moved past, tacking, scarcely using their oars, their small, triangular storm sails beaten from the north. The lateen-rigged galley, whether a round ship or a ram-ship, although it can furl its sail, cannot well let out and take in sail; it is not a square-rigged craft; accordingly she carries different sails for different conditions; the yard itself, from the mast, is lowered and hoisted, sails being removed or attached; the three main types of sail used are all lateens, and differ largely in their size; there is a large, fair-weather sail, used with light winds; there is a smaller sail, used with strong winds astern; and yet a smaller sail, a storm sail, used most often in riding out storms." — Raiders of Gor, page 265.

"Gorean galleys commonly carry several sails, usually falling into three main types, fair-weather, 'tarn' and storm. Within each type, depending on the ship, there may be varieties. The Tesephone carried four sails, one said of the first type; two of the second, and one of the third. Her sails were, first, the fair-weather sail, which is quite large, and is used in gentle winds; secondly, the tarn sail, which is the common sail most often found on the yard of a tarn ship, and taking its name from the ship; third, a sail of the same type as the tarn sail, and, in a sense, a smaller 'tarn' sail, the 'tharlarion' sail; this smaller 'tarn' sail, or 'tharlarion' sail, as it is commonly called, to distinguish it from the larger sail of the same type, is more manageable than the standard, larger tarn sail; it is used most often in swift, brutal, shifting winds, providing a useful sail between the standard tarn sail and the storm sail; fourthly, of course, the Tesephone carried her storm sail; if, upon occasion, a ship could not run before a heavy sea, it would be broken in the crashing of the waves. Gorean galleys, in particular the ram-ships, are built for speed and war. They are long, narrow, shallow-drafted, carvel-built craft. They are not made to lift and fall, to crash among fifty-foot waves, caught in the fists of the sea's violence. In such a sea literally, in spite of their beams and chains, they can break in two, snapping like the spines of tabuk in the jaws of frenzied larls. In changing a sail, the yard is lowered, and then raised again. In the usual Gorean galley, lateen rigged, there is no practical way to take in, or shorten, sail, as with many types of square-rigged craft. In consequence, the different sails. The brail ropes serve little more, in the lateen-rigged galley, with its triangular sail on the long, sloping yard, has marvelous maneuvering capabilities, and can sail incredibly close to the wind. Its efficiency in tacking more than compensates for the convenience of a single, multipurposed sail. And, too, perhaps it should be mentioned, the lateen rigging is very beautiful." — Hunters of Gor, pages 33-34.

Other Sailing Vessels

• Barge

A vessel used to carry goods and passengers across rivers and to navigate the marshes. Marsh barges are typically rowed by slaves.

"In the light of the moving torches, beyond them, toward the marsh, I saw, dark, the high, curved prows of narrow marsh barges, of the sort rowed by slaves." — Raiders of Gor, page 51.

"The high-prowed marsh barge is anchored at both stem and stern. Soon, each drawn by two warriors, the anchor-hooks, curved and three-pronged, not unlike large grappling irons, emerged dripping from the mud on the marsh. These anchor-hooks, incidentally, are a great deal lighter that the anchors used in the long galleys, and the round ships." — Raiders of Gor, page 61.

"The officer, standing on the tiller deck of the flagship, lifted his arm. In marsh barges there is no time-beater, or keleustes, but the count to the oarsmen is given by mouth, by one spoken of as the oar-master. He sits somewhat above the level of the rowers, but below the level of the tiller deck. He, facing the rowers, faces toward the ship's bow, they of course, in their rowing facing the stern." — Raiders of Gor, page 61.

• Punt

A pontoon; a small boat, flat-bottomed and square-ended, which is generally is manned by slaves. These boats move ahead of the marsh barges, the slaves cutting down rushes to clear the path.

Etymology: (assumed) Middle English, from Old English, from Latin ponton-, ponto; Date: before 12th century;

"A long narrow flat-bottomed boat with square ends usually propelled with a pole." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"The oar-master of the sixth barge was doubtless angry. He had had to stop calling his time. The barges in line before him, too, had slowed, then stopped, their oars half inboard, waiting. It is sometimes difficult for even a small rence craft to make its way through the tangles of rushes and sedge in the delta. A punt, from the flagship, moved ahead. Two slaves stood aft in the small, square-ended, flat-bottomed boat, poling. Two other slaves stood forward with gloves, lighter poles, bladed, with which they cut a path for the following barges. That path must needs be wide enough for the beam of the barges, and the width of the stroke of the oars." — Raiders of Gor, page 69.

On Oars and Oarring

The oarring system developed on Gor is very heavily based on the Greek triremes (see: "Trireme" further down the page ). The rowers sit three to a bench; the ship single-banked (level), although it has been known for ships to have double or triple banks of rowers. The oars are generally of two (2) types: the outboard oar, which is the shortest and is furthest from the ship, and the inboard oar, which is the longest and is nearest to the ship. Footbraces are set in front of each bench to allow the rower's maximum leverage. If the rower's are slaves, they are thusly chained to these footbraces.

"Although the Dorna's true beam is sixteen feet Gorean, her deck width is twenty-one feet Gorean, due to the long rectangular rowing frame, which carries the thole ports; the rowing frame is slightly higher than the deck area and extends beyond it, two and one half feet Gorean on each side; it is supported by extensions of the hull beams; the rowing frame is placed somewhat nearer the stem that the sternpost; the extension of the rowing frame not only permits greater deck area but, because of the size of the oars used, is expedient because of matters of work space. — Raiders of Gor, page 193.

The size and weight of the oars used will doubtless seem surprising, but, in practice, they are effective and beautiful levers. The oars are set in groups of three, and three men sit a single bench. These benches are not perpendicular to the bulwarks but slant obliquely back toward the stern castle. Accordingly their inboard ends are father aft than their outboard ends. This slanting makes it possible to have each of the three oars in an oar group parallel to the others. The three oars are sometimes of the same length, but often they are not. The Dorna used oars of varying lengths; her oars, like those of many tarn ships, varied by about one and one-half foot Gorean, oar to oar; the most inboard oar being the longest; the outboard oar being the shortest. The oars themselves usually weigh about one stone a foot, or roughly founds pounds a foot. The length of those oars on a tarn ship commonly varies from twenty-seven to thirty foot Gorean. A thirty-foot Gorean oar, the most inboard oar, would commonly weigh thirty stone, or about one hundred and twenty pounds. The length and weight of these oars would make their operation impractical were it not for the fact that each of them, on its inboard end, is weighted with lead. Accordingly the rower is relieved of the weight of the oar and is responsible only for its work. This arrangement, one man to an oar, and oars in groups of tree, and oars mounted in the rowing frame, long and beautiful sweeps, had been found extremely practical in the Gorean navies. It is almost universal on ram-ships. The rowing deck, further, is open to the air, thereby differing from the rowing holds of round ships. This brings many more free fighting men, the oarsmen, into any action which might be required. They, while rowing, are protected, incidentally, by a parapet fixed on the rowing frame. Between each pair of benches, behind the parapet, is one bowman. The thole ports in a given group of three are about ten inches apart and the groups themselves, center to center, are a bit less than four feet apart. Then Dorna carried twenty groups of three to a side, and so used one hundred and twenty oarsmen." — Raiders of Gor, pages 193-194."From this account it may perhaps be conjectured why the oar power of a single-banked ram-ship is often comparable or superior to that of a doubly- or trebly-banked ship. The major questions involve the number and size of oars that can be practically mounted, balanced against the size of ship required for the differing arrangements. The use of extended rowing frame, permitting the leverage necessary for the great oars, and the seating of several oarsmen, each with his own oar, on a given bench, conserving space, are important in this regard. If we suppose a trebly-banked ship with one hundred and twenty oarsmen, say, in three banks of twenty each to a side, I think we can see she would have to be a rather large ship, and a good deal heavier than the single-decked, three-men-to-a-bench type, also with one hundred and twenty oarsmen. She would thus, also, be slower. And this does not even take into consideration the longer, larger oar possible with the projecting rowing frame. To be sure, they are many factors involved here, and one might suppose triple banks following the model of the single-banked, three-men-oars-to-a-bench type, and so on, but, putting aside questions of the size of vessel required for such arrangements, we may simply note, without commenting further, that the single-banked, three-men-three-oars arrangement is almost universal in fighting ships on Thassa. The other type of ship, though found occasionally, does not seem, at least currently, to present a distinct challenge to the low, swift, single-banked ships. In questions of ramming, I suppose the heavier ship would deliver the heaviest blow, but, even this might be contested for the lighter ship would, presumably, be moving more rapidly. Further, of course, the chances of being rammed by a lighter ship are greater than those of being rammed by a heavier ship, because of the greater speed and maneuverability of the former. Other disadvantages to the double- and triple-banked systems, of course, are that many of your oarsmen, if not all, are below decks and thus unable to enter into necessary actions as easily as they might otherwise do; further, in case of ramming or wreck, it is a good deal more dangerous to be below decks than above decks. At any rate, whatever the reasons or rationale, the single-banked tarn ship, of which the Dorna is an example, is the dominant type on Thassa." — Raiders of Gor, pages 194-195.

"You will not find this an easy ship to row," said the oar-master, chaining my ankles to the heavy footbrace. — Raiders of Gor, page 183.

Oarring Terminology

• Full Oars

Reference to all rower's on a ship.

"Full oars!" cried the oar-master. "Stroke!" — Raiders of Gor, page 186.

• Oars Inboard

The command for rowers to bring their oars inside the ship.

"Oars inboard!" cried the oar-master, instinctively. The oars slid inboard. — Raiders of Gor, page 188.

• Out Oars

Also: Oars Outboard

The command for rowers to slide their oars (through the thole ports) out from the ship.

"Out oars!" called the oar-master. I, with the others, slid my oar outboard. — Raiders of Gor, page 183.

"Oars outboard!" I commanded. Obediently the oars slid outboard, and suddenly, all along the starboard side there was a great grinding, and the slaves screamed, and there was a sudden ripping of planks and a great snapping and splintering of wood, the sounds magnified, thunderous and deafening, within the wooden hold. — Raiders of Gor, page 188.

• Port Oars

Reference to the rower's on the port side of a ship.

"Up oars!" cried the oar-master. "Port Oars! Stroke!" We lifted our oars, and then those of the port side only entered the water and pressed against it. In a few strokes the heavy Rena had swung some eight points, by the Gorean compass, to starboard. — Raiders of Gor, page 186.

• Ready Oars

Rower's prepare and poise oars waiting for the command to begin rowing.

"Ready oars!" called the oar-master. The oars were poised. — Raiders of Gor, page 183.

• Stroke

The command for rowers to row.

"Stroke!" called the oar-master. The keleustes struck the great copper drum before him with the leather-cushioned mallet. As one the oars entered the water, dipping and moving within it. My feet thrust against the footbrace and I drew on the oar. — Raiders of Gor, pages 183-184.

Nautical Terminology

Nautical: "The steering gear of a ship, especially the tiller or wheel." — The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition ©2000.

• Aft

Toward the stern (rear) of a ship.

Etymology: Middle English afte back, from Old English æftan from behind, behind; akin to Old English æfter; Date: 1628;

"Near, toward, or in the stern of a ship." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"The slaves, like fish, were thrown between the rowers benches, and aft, forward of the tiller deck, three or four deep." — Raiders of Gor, page 60.

"A punt, from the flagship, moved ahead. Two slaves stood aft in the small, square-ended, flat-bottomed boat, poling." — Raiders of Gor, page 69.

"The size and weight of the oars used will doubtless seem surprising, but, in practice, they are effective and beautiful levers. The oars are set in groups of three, and three men sit a single bench. These benches are not perpendicular to the bulwarks but slant obliquely back toward the stern castle. Accordingly their inboard ends are father aft than their outboard ends. This slanting makes it possible to have each of the three oars in an oar group parallel to the others." — Raiders of Gor, pages 193-194.

• Anchor Hooks

Similar to grappling irons, used as anchoring devices for marsh barges.

"The high-prowed marsh barge is anchored at both stem and stern. Soon, each drawn by two warriors, the anchor-hooks, curved and three-pronged, not unlike large grappling irons, emerged dripping from the mud on the marsh. These anchor-hooks, incidentally, are a great deal lighter that the anchors used in the long galleys, and the round ships." — Raiders of Gor, page 61.

• Arsenal

With respect to Port Kar, this is in reference to their warehouses in which ships, sails, equipment and weapons are manufactured and stored.

Etymology: Italian arsenale, ultimately from Arabic dAr sinA'ah house of manufacture; Date: 1555;

"An establishment for the manufacture or storage of arms and military equipment." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"The next matter for consideration was the negotiation of a dispute between the sail-makers and the rope-makers in the arsenal with respect to priority in the annual Procession to the Sea, which takes place on the first of En'Kara, the Gorean New Year." — Raiders of Gor, page 134.

• Arsenal Guard

The military force responsible for keeping safe the arsenal of Port Kar.

"The Arsenal Guard, however, perhaps for traditional reasons, remained a separate body, concerned with the arsenal, and having jurisdiction within its walls." — Raiders of Gor, page 218.

• Brail Rope

Rope used in the common lateen-rigged Gorean galley to raise the sail to its yard, to be secured there, or lower the sail to open it to the winds. Lateen rigging (a single, triangular sail) is preferred because of the excellent maneuverability lateen rigging provides.

"Rope which gathers up a sail to furl it." — Waterways Object Name Thesaurus

brail

1. One of several small ropes attached to the leech of a sail for drawing the sail in or up.

2. A small net for drawing fish from a trap or a larger net into a boat.

brailed, brail-ing, brails

1. To gather in (a sail) with brails.

2. To haul in (fish) with a brail. — The Free Dictionary by Farlex

"Men scrambled on the long yard of the lateen-rigged light galley, a small, swift ram-ship of Port Kar. Others, on the deck, hauled on the long brail ropes. Slowly, billow by billow, the sails were furled. We would not remove them from the yard. The yard itself was then swung about, parallel to the ship and, foot by foot, lowered. We did not lower the mast. It remained deep in its placement blocks. We were not intending battle. The oars were now inboard, and the galley, of its own accord, swung into the wind. … — Hunters of Gor, page 34.

"In the usual Gorean galley, lateen rigged, there is no practical way to take in, or shorten, sail, as with many types of square-rigged craft. In consequence, the different sails. The brail ropes serve little more, in the lateen-rigged galley, with its triangular sail on the long, sloping yard, has marvelous maneuvering capabilities, and can sail incredibly close to the wind." — Hunters of Gor, page 34.

• Builder's Glass

The Telescope of Gor.

"The man carried a long glass of the builders." — Raiders of Gor, page 185.

"From the stern castle of the Dorna, then, with a long glass of the builders, I observed, far across the waters, the masts of ram-ships, one by one, lowering." — Raiders of Gor, page 197.

"As the beat dropped, I took out the glass of the builders and scanned the horizon." — Raiders of Gor, page 201.

"I was given my Admiral's cloak and I flung this over my shoulder, my left, that to which the strap carrying the glass of the builders was attached. I then thrust some strips of dried tarsk meat in my belt. I called the lookout down from the basket, that I might climb to his place. In the basket I wrapped the admiral's cloak about me, began to chew on a piece of tarsk meat, as much against the cold as the hunger, and took out the glass of the builders." — Raiders of Gor, page 265.

"I let the builders' glass, attached to the strap about my shoulder, fall to my side." — Raiders of Gor, page 271.

• Carvel-Built

Refers to the method of ship building; in a carvel-built ship, the ship is built from wooden planks with flush seams.

Etymology: probably from Dutch karveel-, from karveel caravel, from Middle French carvelle; Date: 1798;

"Built with the planks meeting flush at the seams." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"She is carvel-built, and her planking is fastened with nails of bronze and iron; in places, wooden pegs are also used; her planking, depending on placement, varies from two to six inches in thickness; also, to strengthen her against the shock of ramming, four-inch-thick wales run longitudinally about her sides." — Raiders of Gor, page 192.

• Caulking

Substance used to seal boat seams.

Etymology: Middle English caulken, from Old North French cauquer to trample, from Latin calcare, from calc-, calx heel; Date: 15th century;

"To stop up and make tight against leakage (as a boat or its seams, the cracks in a window frame, or the joints of a pipe)." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"It was voted that another dozen covered docks be raised within the confines of the arsenal, that the caulking schedule of the grand fleet might be met." — Raiders of Gor, page 134.

• First Oar

The person placed at the first oar (thwart); always the strongest of the men.

"Clitus was slighter, but he had been first oar; he would have great strength, beyond what it might seem." — Raiders of Gor, page 89.

"I looked down to the slave at the starboard side, he at the first thwart, who would be first oar." — Raiders of Gor, page 83.

• Flags of Division and Acquisition

Considering that division means to separate, and acquisition means to come into possesion of, these flags, utilized by pirates, and perhaps other raiders, to make known to another ship (or ships) of intent to claim their ships and goods.

"Thurnock," I said, "let the flags of division and acquisition be raised." — Raiders of Gor, page 206.

• Flagship

The ship in a fleet which flies the flag of the admiral.

"The officer, standing on the tiller deck of the flagship, lifted his arm." — Raiders of Gor, page 61.

"And the flag she flew was bordered with gold, the admiral's flag, marking that vessel as the flagship of the treasure fleet." — Raiders of Gor, page 206.

"I received her in the admiral's cabin, which was, of course, on the treasure fleet's flagship." — Raiders of Gor, page 206.

• Freeboard Area

The distance between the waterline and the main deck of a ship.

Date: 1726;

"The distance between the waterline and the main deck or weather deck of a ship or between the level of the water and the upper edge of the side of a small boat." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"The Dorna, like most tarn ships, is a long, narrow vessel of shallow draft. She is carvel-built, and her planking is fastened with nails of bronze and iron; in places, wooden pegs are also used; her planking, depending on placement, varies from two to six inches in thickness; also, to strengthen her against the shock of ramming, four-inch-thick wales run longitudinally about her sides. She carries a single, removable mast, with its long yard. It is lateen rigged. Her keep, one hundred and twenty-eight feet Gorean, and her beam, sixteen feet Gorean, mark her as heavy class. Her freeboard area, that between the water line and the deck, is five feet Gorean." — Raiders of Gor, page 192.

• Furl the Sail

Command to draw in the sail.

"Furl the sail," I told an officer. He began to cry orders to the seamen. Soon seamen were clambering out on the long sloping yard and, assisted by others on the deck, hauling on brail ropes, were tying in the long triangular sail. — Raiders of Gor, page 264.

• Galley Slaves

Generally male prisoners which labor as oarmen in the galleys of ships.

"… a galley slave… The great merchant galleys of Port Kar, and Cos, and Tyros, and other maritime powers, utilized thousands of such miserable wretches, fed on brews of peas and black bread, chained in the rowing holds, under the whips of slave masters, their lives measured by feedings and beatings, and the labor of the oar." — Hunters of Gor, page 13.

"Then, after a time, the last of the slaves had been secured and placed on the barges. The slaves of the men of Port Kar then separated the nets, rolling them, then folding them, then placing them on the barges. They then drew up the planks and took their seats at the rowers' benches, to which, unprotesting, one by one, they were shackled." — Raiders of Gor, page 61.

• Helmsman

Just as on earth, a nautical term to denote the one whose job it is to tend the tiller of a boat, thus steering it; the steersman.

"A person who steers a ship." — The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition ©2000.

"The oar-master cried out angrily and turned to the helmsman, he who held the tiller beam. The helmsman stood at the tiller, not moving. He had removed his helmet in the noon heat of the delta. Insects, undistracted, hovered about his head, moving in his hair. The oar-master, crying out, leaped up the stairs to the tiller deck, and angrily seized the helmsman by the shoulders, shaking him, then saw his eyes." — Raiders of Gor, page 69.

• Keleustes

One who counts the time for the rowers; also referred to as the Time-Beater.

"The officer, standing on the tiller deck of the flagship, lifted his arm. In marsh barges there is no time-beater, or keleustes, but the count to the oarsmen is given by mouth, by one spoken of as the oar-master." — Raiders of Gor, page 61.

"He turned the key in the locks and, laughing, turned about and went to his seat, facing us, in the stern of the rowing hold. Before him, since this was a large ship, there sat a keleustes, a strong man, a time-beater, with leather-wrapped wrists. He would mark the rowing stroke with blows of wooden, leather-cushioned mallets on the head of a huge copper-covered drum." — Raiders of Gor, page 183.

• Message Flags

Flags raised on ships which display various messages, i.e., truce.

"Message flags, doubtless repeating the message of the trumpets, were being run from the decks on their halyards to the heights of the stem castles." — Raiders of Gor, page 197.

"… I had communicated with my other ships by flag and trumpet, some of them conveying my messages to others more distant." — Raiders of Gor, page 205.

• Mooring Cleat

Used to tether boats.

Mooring:Date: 15th century;

1. An act of making fast a boat or aircraft with lines or anchors;

2. A place where or an object to which something (as a craft) can be moored;

3. A device (as a line or chain) by which an object is secured in place." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.Moor:Etymology: Middle English moren; akin to Middle Dutch meren, maren to tie; Date: 15th century;

Transitive Senses:

"To make fast with or as if with cables, lines, or anchors."

Intransitive senses:

1. to secure a boat by mooring;

2. to be made fast." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.Cleat: Etymology: Middle English clete wedge, from (assumed) Old English clEat; akin to Middle High German klOz lump; Date: 14th century;

1. A wedge-shaped piece fastened to or projecting from something and serving as a support or check;

2. A wooden or metal fitting usually with two projecting horns around which a rope may be made fast." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"Telima, kneeling bound below me, on the left, the binding fiber on her throat, tethered to the mooring cleat, looked up at me." — Raiders of Gor, page 85.

• Nails

Made of bronze and iron, used in the building of ships.

"The Dorna, like most tarn ships, is a long, narrow vessel of shallow draft. She is carvel-built, and her planking is fastened with nails of bronze and iron; in places, wooden pegs are also used; her planking, depending on placement, varies from two to six inches in thickness; also, to strengthen her against the shock of ramming, four-inch-thick wales run longitudinally about her sides." — Raiders of Gor, page 85.

• Oar-Master

Keeps the pace of the rowers.

"The officer, standing on the tiller deck of the flagship, lifted his arm. In marsh barges there is no time-beater, or keleustes, but the count to the oarsmen is given by mouth, by one spoken of as the oar-master. He sits somewhat above the level of the rowers, but below the level of the tiller deck. He, facing the rowers, faces toward the ship's bow, they of course, in their rowing facing the stern. The officer on the tiller deck, Henrak at his side, let fall his hand.I heard the oar-master cry out and I saw the oars, with a sliding of wood, emerge from the thole ports. They stood poised, parallel, over the water, the early-morning sun illuminating their upper surfaces. I noted that they were no more than a foot above the water, so heavily laden was the barge. Then, as the oar-master again cried out, they entered as one into the water; and the, as he cried out again, ear oar drew slowly in the water, and then turned and lifted, the water falling in the light from the blades like silver chains.

The barge, deep in the water, began to back away from the island. Then, some fifty yards away, it turned slowly, prow now facing away from the island, toward Port Kar. I heard the oar-master call his time again and again, not hurrying his men, each time more faintly than the last. Then the second barge backed away from the island, turned and followed the first, and then so, too, did the others." — Raiders of Gor, pages 61-62.

• Oar Shearing

Naval strategy commonly used; ships are equipped with shearing blades, which can devastate an enemy ship. See also: "Shearing Blades."

"Indeed, the galleys of Port Kar, medium and heavy class, carried shearing blades, which had been an invention of Tersites. These are huge quarter-moons of steel, fixed forward of the oars, anchored into the frame of the ship itself. One of the most common of naval strategies, other than ramming, is oar shearing, in which one vessel, her oars suddenly shortened inboard, slides along the hull of another, whose oars are still outboard, splintering and breaking them off. The injured galley then is like a broken-winged bird, and at the mercy of the other ship's ram as she comes about, flutes playing and drums beating, and makes her strike amidships. Recent galleys of Cos and Tyros, and other maritime powers, it had been noted, were now also, most often, equipped with shearing blades." — Raiders of Gor, pages 136-137.

"They are going to shear!" came a cry from above board.

"Oars inboard!" cried the oar-master, instinctively. The oars slid inboard.

"Oars outboard!" I commanded.

Obediently the oars slid outboard, and suddenly, all along the starboard side there was a great grinding, and the slaves screamed, and there was a sudden ripping of planks and a great snapping and splintering of wood, the sounds magnified, thunderous and deafening, within the wooden hold. Some of the oars were torn from the thole ports, others were snapped off or half broken, the inboard portions of their shafts, with their looms, snapping in a sternward arc, knocking slaves from the benches, cracking against the interior of the hull planking. I heard some men cry out in pain, ribs or arms broken. For an ugly moment the ship canted sharply to starboard and we shipped water through the thole ports, but then the other ship, with her shearing blade, passed, and the Rena righted herself, but rocked helplessly, lame in the water. — Raiders of Gor, page 188.

• Pincer Blade

Nautical military tactic in which two forces converge on the opposite sides of an enemy's position.

Etymology: Middle English pinceour, from (assumed) Anglo-French pinceour, from Middle French pincier to pinch, from (assumed) Vulgar Latin pinctiare, punctiare, from Latin punctum puncture; Date: 14th century;

"One part of a double envelopment in which two military forces converge on opposite sides of an enemy position." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"My fifth wave was divided into two portions, the pincer blade striking from the north under the command of the tall, long-haired Nigel, with his fifteen ships, supplemented by twenty-five of the arsenal, and the pincer blade from the south under the command of Chung, with his twenty ships, supplemented by another twenty, from the arsenal. All of these ships were tarn ships." — Raiders of Gor, pages 269-270.

• Port

The left side of a ship. However, though Tarl uses this term, it seems the expression "port" is not a part of the Gorean language, though there is an equivalent in Gorean, though he does not provide that information.

Date: circa 1625;

"The left side of a ship or aircraft looking forward." — Merriam-Webster Dictionary ©2002-2006.

"Up oars!" cried the oar-master. "Port Oars! Stroke!" We lifted our oars, and then those of the port side only entered the water and pressed against it. In a few strokes the heavy Rena had swung some eight points, by the Gorean compass, to starboard. — Raiders of Gor, page 186.

"The new vessel was abeam on our port side. Sailors of Cos usually refer to the left side of the ship by the port of destination and the right side of the ship by the port of registration; this alters, of course, when the ports of destination and registration are the same; in that case the sailors of Cos customarily refer to the left side of the ship as the 'harbor side,' the right side of the ship normally continuing to be designated as before, by reference to the port of registration. This sort of thing occasionally presents problems in translation between Gorean and English." — Slave Girl of Gor, page 362.

• Procession to the Sea

On each Gorean New Year, the captains of the ships in Port Kar sail to the Sea.

"The next matter for consideration was the negotiation of a dispute between the sail-makers and the rope-makers in the arsenal with respect to priority in the annual Procession to the Sea, which takes place on the first of En'Kara, the Gorean New Year." — Raiders of Gor, page 134.

• Prow Girl

On Merchant ships, and even on warships, if luck has it that one of the spoils is a beautiful girl, this girl is chained to the prow of the ship, so that as the ship returns home, the captain's wealth, vanity and pride is displayed.

""The Lady Vivina," I said to him, "will of course grace the prow of this ship, the flagship of the treasure fleet." — Raiders of Gor, page 209.

"Take then those that were with her," I said, "and distribute them to the extent of their number among our other ships, the twenty most beautiful to our twenty tarn ships now with the fleet, and the most beautiful of the twenty to the prow of the Dorna, and the other twenty set at the prows of twenty of our prizes. — Raiders of Gor, page 209.

• Shearing Blades