Wagon Peoples

Geography & Climate

The Plains of Turia

The Wagon Peoples claim the Plains of Turia as their own. I think, when some picture "The Plains of Turia" they see a plot of land about 1/16th the size of Kansas; I picture the State of Texas — and then some. In actuality these plains consume a large portion of the southern continent of Gor, extending from the Thassa (the Sea) and the Ta-Thassa Mountains and down to the Voltai Range. The Wagon Peoples also claim land to the north, as far up as the Cartius River, named for the direction it lies from the city of Ar.

"The Wagon Peoples claimed the southern prairies of Gor, from the gleaming Thassa and the mountains of Ta-Thassa to the southern foothills of the Voltai Range itself, that reared in the crust of Gor like the backbone of a planet. On the north they claimed lands even to the rush-grown banks of the Cartius, a broad, swift flowing tributary feeding into the incomparable Vosk." — Nomads of Gor, page 2.

"The Cartius River incidentally, mentioned earlier, was named for the direction it lies from the city of Ar. From the Sardar I had gone largely Cart, sometimes Vask, then Cart again until I had come to the Plains of Turia, or the Land of the Wagon Peoples." — Nomads of Gor, page 3 (footnote).

Trees No Where to Be Found

Much to the consternation of many, the southern plains are treeless.

"I was afoot, on the treeless southern plains of Gor, on the Plains of Turia, in the Land of the Wagon Peoples." — Nomads of Gor, page 9.

Except for Turia, it seems. Turia was purportedly named for the one, lone Tur tree found on the entire plains (amazing, huh?). Though it seems that the Tur tree within the garden in Turia described below was not the tree.

It could be conjectured that when the city was founded, trees and other plant-life were imported from other parts of the planet. The trees noted in Turia were a part of the gardens of the House a Saphrar. That, then, makes the conjecture of the import of trees quite feasible.

And so we sat with our backs against the flower tree in the House of Saphrar, merchant of Turia. I looked at the lovely, dangling loops of interwoven blossoms which hung from the curved branches of the tree. I knew that the clusters of flowers which, cluster upon cluster, graced those linear, hanging stems, would each be a bouquet in itself, for the trees are so bred that the clustered flowers emerge in subtle, delicate patterns of shades and hues. Besides several of the flower trees there were also some Ka-la-na trees, or the yellow wine trees of Gor; there was one large-bunked, reddish Tur tree, about which curled its assemblage of Tur-Pah, a vinelike tree parasite with curled, scarlet, ovate leaves, rather lovely to look upon; the leaves of the Tur-Pah incidentally are edible and figure in certain Gorean dishes, such as sullage, a kind of soup; long ago, I had heard, a Tur tree was found on the prairie, near a spring, planted perhaps long before by someone who passed by; it was from that Tur tree that the city of Turia took its name; there was also, at one side of the garden, against the far wall, a grove of tem-wood, linear, black, supple. Besides the trees there were numerous shrubs and plantings, almost all flowered, sometimes fantastically; among the trees and the colored grasses there wound curved, shaded walks. Here and there I could hear the flowing of water, from miniature artificial waterfalls and fountains. From where I sat I could see two lovely pools, in which lotuslike plants floated; one of the pools was large enough for swimming; the other, I supposed, was stocked with tiny, bright fish from the various seas and lakes of Gor." — Nomads of Gor, pages 217-218.

The Climate

The plains are almost desert-like, with its intense heat of the summer months and the deep chill of the winter months. Even the spring time, though somewhat mild, still has a chill to the air. However, Tarl Cabot discovered that the Tuchuks did not particularly notice the chill of the air or let it bother them.

"Although it was late in the afternoon the sun was still bright. The air was chilly. There was a bit of wind moving the grass." — Nomads of Gor, page 80.

"I was chilly in the spring night and my clothes, of course, were soaked. Harold did not seem to notice or mind this inconvenience. The Tuchuks, to my irritation, tended on the whole not to notice or mind such things." — Nomads of Gor, page 192.

The winters on the plains can be furious and deadly, however, and the tribes must move northward to the equatorial areas so that the bosk can survive the winter months, having food to sustain them. Still, even though they migrate north, the winters are still very chilly and the Wagon Peoples, slave and free alike, must wear clothing to protect them.

The winter came fiercely down on the herds some days before expected, with its fierce snows and the long winds that sometimes have swept twenty-five hundred pasangs across the prairies; snow covered the grass, brittle and brown already, and the herds were split into a thousand fragments, each with its own riders, spreading out over the prairie, pawing through the snow, snuffing about, pulling up and chewing at the grass, mostly worthless and frozen. The animals began to die and the keening of women, crying as though the wagons were burning and the Turians upon them, carried over the prairies. Thousands of the Wagon Peoples, free and slave, dug in the snow to find a handful of grass to feed their animals. Wagons had to be abandoned on the prairie, as there was no time to train new bosk to the harness, and the herds must needs keep moving.

At last, seventeen days after the first snows, the edges of the herds began to reach their winter pastures far north of Turia, approaching the equator from the south. Here the snow was little more than a frost that melted in the afternoon sun, and the grass was live and nourishing. Still farther north, another hundred pasangs, there was no snow and the peoples began to sing and once more dance about their fires of bosk dung.

"The bosk are safe," Kamchak had said. I had seen strong men leap from the back of the kaiila and, on their knees, tears in their eyes, kiss the green, living grass. "The bosk are safe," they had cried, and the cry had been taken up by the women and carried from wagon to wagon, "The bosk are safe" This year, perhaps because it was the Omen Year, the Wagon Peoples did not advance farther north than was necessary to ensure the welfare of the herds. They did not, in fact, even cross the western Cartius, far from cities, which they often do, swimming the bosk and kaiila, floating the wagons, the men often crossing on the backs of the swimming bosk. — Nomads of Gor, page 58-59."The Wintering was not unpleasant, although, even so far north, the days and nights were often quite chilly; the Wagon Peoples and their slaves as well, wore boskhide and furs during this time; both male and female, slave or free, wore furred boots and trousers, coats and the flopping, ear-flapped caps that tied under the chin; in this time there was often no way to mark the distinction between the free woman and the slave girl, save that the hair of the latter must needs be unbound; in some cases, of course, the Turian collar was visible, if worn on the outside of the coat, usually under the furred collar; the men, too, free and slave, were dressed similarly, save that the Kajiri, or he-slaves, wore shackles, usually with a run of about a foot of chain." — Nomads of Gor, page 59.

A Lesson in Geography and Climates

Unless you're a big history and geography buff like me, understanding why the herds move northward rather than south can get a bit confusing. Most of us live in the northern hemisphere on Earth, and we think of migrating as the Canadian geese flying south to warmer climates and old folks hurrying from their homes in New England to the warm pleasures of Florida.

When you live in the southern hemisphere, everything is flipped; it is a mirror-opposite of what we know up here in the northern half. For example, while we're looking outside at the snow on Christmas Day, our friends down under in Australia are unwrapping their gifts in the heat of summer.

|

|

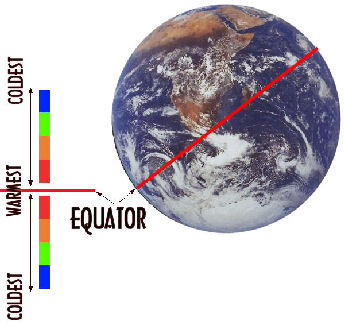

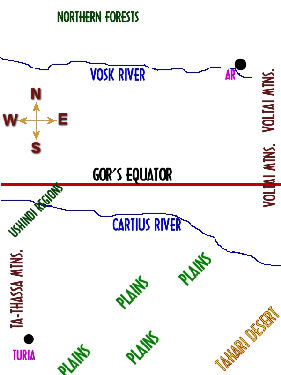

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

Let's look at Figure 1. This is a representation of the planet; the red line being that of the equator. If you look to the left, I've created a chart to demonstrate the climate in relation to the equator. If you look, from the equator line, moving north, when you reach the peak, you are at the arctic region, the coldest point in the northern hemisphere. If you look from the equator line and move south, you will eventually come to the sub-arctic (or antarctic) region, the coldest point in the southern hemisphere. The sub-arctic is far colder than the arctic region.

Figure 2 is my rather crude depiction of Gor. I didn't make it pretty or to scale; I simply wanted to demonstrate where the Wagon Peoples are located in relation to other points, and especially to the equator. If you see, Turia also lies far south of the equator. Therefore, when the Wagon Peoples leave the plains south of Turia, they first must pass Turia (the Passing of Turia), before moving north-eastward to the wintering grounds near and sometimes above the Cartius River.

Such is probably relative to the Eastern and Western Steppes of Eurasia in the times of the nomadic tribes such as the Huns, the Avars, the Mongols, et al.

![]()

Special Note

Because of the differences in publishing the books, depending upon whether published in the U.S. or Europe, depending upon whether a first publishing or a Masquerade Books release, page numbers will often vary. All of my quotes are from original, first-printing U.S. publications (see The Books page for a listing of publishers and dates) with the exception of the following books:

- Tarnsman of Gor (2nd Printing, Balantine)

- Outlaw of Gor (11th Printing, Balantine)

- Priest-Kings of Gor (2nd Printing, Balantine)

- Assassin of Gor (10th Printing, Balantine)

- Raiders of Gor (15th Printing, Balantine)

- Captive of Gor (3rd Printing, Balantine)

Disclaimer

These pages are not written for any specific home, but rather as informational pages for those not able to get ahold of the books and read them yourself. Opinions and commentaries are strictly my own personal views, therefore, if you don't like what you are reading — then don't. The information in these pages is realistic to what is found within the books. Many sites have added information, assuming the existences of certain products and practices, such as willowbark and agrimony for healing, and travel to earth and back for the collection of goods. I've explored the books, the flora, the fauna, and the beasts, and have compiled from those mentioned, the probabilities of certain practices, and what vegetation mentioned in the books is suitable for healing purposes, as well as given practicalities to other sorts of roleplaying assumptions.